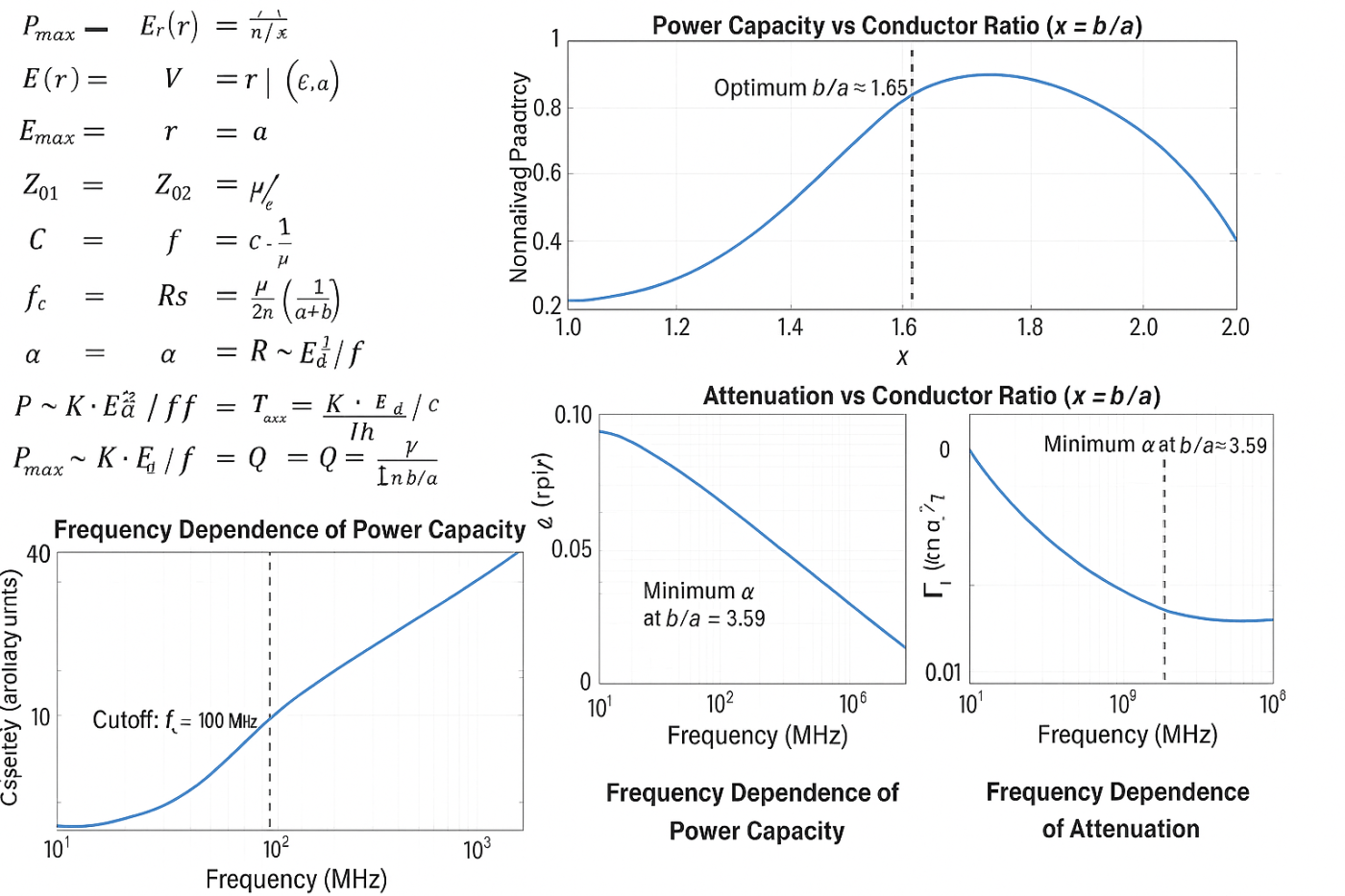

You don’t pick a coax just by the datasheet. You pick it by what you want to carry, how far, how hot, and at what cost. This paper reminds us: power isn’t an abstract number—it’s the outcome of geometry, materials, and frequency conspiring together. And if you’re building systems (or teaching them), the crux is in the trade-offs.

Below is a concise blog-style walkthrough of the paper’s insights, followed by a single Python script that implements the equations so you can explore the design space hands-on.

The deeper truth: you design coax by choosing your compromises. Maximum power isn’t free; it comes with thermal, capacitance, and impedance consequences you must steward.

I love this framing because it elevates designers from “what’s the spec” to “what’s the balance.” It’s stewardship of constraints—engineering as care.

This single script implements the core relationships presented in the paper, with careful unit handling and explanatory docstrings. You can tweak parameters (conductor sizes, dielectric, frequency) and explore the trade-offs.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Coaxial transmission line analysis – one-script implementation

Based on the equations and relationships discussed in:

"Analyzing the Power Handling Capability of a Coaxial Transmission Line" (2016)

Notes:

- This script focuses on the relationships used/mentioned in the paper.

- Some equations appear in stylized/summary form; where needed, standard forms consistent

with the text are used and documented.

- Units are made explicit. Be consistent when calling functions.

Author: Copilot (for Cads)

"""

import math

from dataclasses import dataclass

# Physical constants

C0 = 299_792_458.0 # speed of light in vacuum [m/s]

MU0 = 4e-7 * math.pi # permeability of free space [H/m]

EPS0 = 8.854187817e-12 # permittivity of free space [F/m]

ED_AIR = 3e6 # electric breakdown field of air [V/m] (paper uses ~3e6 V/m)

COPPER_SIGMA = 5.8e7 # conductivity of copper [S/m]

# Conversions

INCH_TO_M = 0.0254

M_TO_INCH = 1 / INCH_TO_M

LOG10 = math.log10

@dataclass

class Coax:

"""

Coaxial line geometry and materials.

Attributes:

a (float): inner conductor radius [m]

b (float): outer conductor inner radius [m]

er (float): relative permittivity of dielectric (ε_r)

ur (float): relative permeability (μ_r), typically ~1 for non-magnetic dielectrics

sigma (float): conductor conductivity [S/m], default copper

k_thermal (float): thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] of dielectric (for conduction model)

"""

a: float

b: float

er: float = 1.0

ur: float = 1.0

sigma: float = COPPER_SIGMA

k_thermal: float = 0.3 # example value used in the paper's conduction plots

# --------------------------

# Geometry & field relations

# --------------------------

def electric_field_radial(V: float, r: float, a: float, b: float) -> float:

"""

Radial electric field magnitude in a coax (quasi-static), E(r) = V / (r * ln(b/a)).

Args:

V: applied voltage [V]

r: radial position [m], a <= r <= b

a: inner conductor radius [m]

b: outer conductor inner radius [m]

Returns:

E(r) [V/m]

"""

return V / (r * math.log(b / a))

def max_surface_e_field(V: float, a: float, b: float) -> float:

"""

Maximum electric field occurs at r = a: E_max = V / (a * ln(b/a))

"""

return V / (a * math.log(b / a))

# --------------------------

# Impedance and capacitance

# --------------------------

def z0_from_geometry(er: float, a: float, b: float) -> float:

"""

Characteristic impedance approximation from geometry:

Z0 ≈ (60 / sqrt(ε_r)) * ln(b/a) [Ohms]

"""

return 60.0 / math.sqrt(er) * math.log(b / a)

def v_prop_fraction(er: float) -> float:

"""

Velocity of propagation fraction vs. c0:

v_prop = c0 / sqrt(ε_r)

Returns: fraction of c0

"""

return 1.0 / math.sqrt(er)

def z0_from_vprop(er: float, a: float, b: float) -> float:

"""

Alternate impedance form (as mentioned in the paper via vendor equation):

Z0 ≈ 138 * Vprop * log10(b/a), with Vprop = 1/sqrt(ε_r)

"""

return 138.0 * v_prop_fraction(er) * LOG10(b / a)

def capacitance_pF_per_in(er: float, a_in: float, b_in: float) -> float:

"""

Capacitance per inch (paper’s empirical-style formula):

C [pF/in] = 7.36 * ε_r * log10(b/a)

Args:

er: relative permittivity

a_in, b_in: radii in inches

"""

return 7.36 * er * LOG10(b_in / a_in)

# --------------------------

# Frequency and cutoff

# --------------------------

def fc_cutoff_hz(a: float, b: float, er: float) -> float:

"""

Paper’s cutoff relation (as stated): fc ≈ c / ((b + a) * sqrt(ε_r))

Returns fc in Hz.

"""

return C0 / ((b + a) * math.sqrt(er))

def power_vs_frequency(Ed_air: float, f_hz: float) -> float:

"""

Paper’s relation: P ∝ (Ed_air^2) / f

Implement as: P = K * (Ed_air^2) / f, with K = 5.3e12 (paper’s scaling).

Returns power in arbitrary units consistent with the paper’s scaling.

"""

K = 5.3e12

return K * (Ed_air ** 2) / f_hz

def power_vs_fc(Ed_air: float, fc_hz: float) -> float:

"""

Maximum power using cutoff frequency (paper): Pmax = K * (Ed_air^2) / fc

"""

K = 5.3e12

return K * (Ed_air ** 2) / fc_hz

# --------------------------

# Attenuation (conductor loss)

# --------------------------

def surface_resistance(f_hz: float, mu_r: float, sigma: float) -> float:

"""

Surface resistance Rs ≈ sqrt(π f μ / σ), μ = μ0 * μ_r

"""

mu = MU0 * mu_r

return math.sqrt(math.pi * f_hz * mu / sigma)

def attenuation_nepers_per_m_simplified(f_hz: float, fc_hz: float) -> float:

"""

Paper provides a compact relation (Eq. 11):

α (nepers) ≈ 0.044 * (fc / c) * sqrt(f)

Because units are stylized in the text, we keep this as a helper to explore trends

rather than absolute calibrated values. Returns nepers/m in a scaled sense.

"""

return 0.044 * (fc_hz / C0) * math.sqrt(f_hz)

def attenuation_conductor_nepers_per_m(f_hz: float, coax: Coax) -> float:

"""

Conductor attenuation approximation using Rs and geometry (trend-based):

α_c ≈ (Rs / (Z0)) * (1/(2π)) * (1/a + 1/b) [nepers/m]

This is a heuristic consistent with many coax loss trends: higher Rs, tighter conductors -> higher loss.

"""

z0 = z0_from_geometry(coax.er, coax.a, coax.b)

rs = surface_resistance(f_hz, coax.ur, coax.sigma)

geom_factor = (1.0 / coax.a + 1.0 / coax.b) / (2.0 * math.pi)

return (rs / z0) * geom_factor

# --------------------------

# Power capacity vs geometry

# --------------------------

def normalized_power_ba_ratio(x: float) -> float:

"""

Paper’s normalized power form: P ∝ ln(x) / x^2, maximized at x ≈ 1.65.

Returns a normalized value (unitless).

"""

if x <= 1.0:

return 0.0

return math.log(x) / (x ** 2)

def optimal_b_over_a_for_power() -> float:

""" Returns ~1.65 (paper’s optimum) """

return 1.65

def ba_for_min_loss() -> float:

""" Returns ~3.59 (paper’s minimum attenuation point) """

return 3.59

# --------------------------

# Thermal conduction (cylindrical shell)

# --------------------------

def heat_transfer_rate_Q(a: float, b: float, k_thermal: float, L_m: float, To_K: float, Ti_K: float) -> float:

"""

Heat conduction through cylindrical shell:

Q = -2π k L (To - Ti) / ln(b/a) [Watts]

"""

return -2.0 * math.pi * k_thermal * L_m * (To_K - Ti_K) / math.log(b / a)

# --------------------------

# Helpers and examples

# --------------------------

def inches_to_m(val_inch: float) -> float:

return val_inch * INCH_TO_M

def m_to_inches(val_m: float) -> float:

return val_m * M_TO_INCH

def demo():

"""

Demonstration of key calculations using the paper’s scenario:

- Compare air vs polyethylene dielectric

- Use b/a ~ 1.65 for max power

- Evaluate cutoff frequency, impedance, capacitance, attenuation, and thermal

"""

print("=== Coax Analysis Demo ===")

# Geometry from the paper’s example:

# Air-filled: b = 0.36 in, a chosen near max power range (e.g., 0.12 in <= a < b)

# Polyethylene-filled: b = 0.24 in, a ≈ 0.075 in <= a < b

b_air_in = 0.36

a_air_in = 0.12

b_pe_in = 0.24

a_pe_in = 0.075

b_air = inches_to_m(b_air_in)

a_air = inches_to_m(a_air_in)

b_pe = inches_to_m(b_pe_in)

a_pe = inches_to_m(a_pe_in)

# Dielectrics

er_air = 1.0

er_pe = 2.25 # typical value used in the paper

# Define coaxes

coax_air = Coax(a=a_air, b=b_air, er=er_air, ur=1.0, sigma=COPPER_SIGMA, k_thermal=0.3)

coax_pe = Coax(a=a_pe, b=b_pe, er=er_pe, ur=1.0, sigma=COPPER_SIGMA, k_thermal=0.3)

# b/a ratio check

x_air = b_air / a_air

x_pe = b_pe / a_pe

print(f"Air b/a: {x_air:.2f}, normalized power ~ {normalized_power_ba_ratio(x_air):.4f}")

print(f"PE b/a: {x_pe:.2f}, normalized power ~ {normalized_power_ba_ratio(x_pe):.4f}")

print(f"Optimal b/a for max power: {optimal_b_over_a_for_power():.2f}")

print(f"b/a for min attenuation: {ba_for_min_loss():.2f}")

print()

# Impedance

z0_air = z0_from_geometry(er_air, a_air, b_air)

z0_pe = z0_from_geometry(er_pe, a_pe, b_pe)

print(f"Z0 (air): {z0_air:.2f} Ω")

print(f"Z0 (PE ): {z0_pe:.2f} Ω")

print()

# Capacitance (pF/in)

c_air_pfin = capacitance_pF_per_in(er_air, a_air_in, b_air_in)

c_pe_pfin = capacitance_pF_per_in(er_pe, a_pe_in, b_pe_in)

print(f"C per inch (air): {c_air_pfin:.2f} pF/in")

print(f"C per inch (PE ): {c_pe_pfin:.2f} pF/in")

print()

# Cutoff frequency (Hz)

fc_air = fc_cutoff_hz(a_air, b_air, er_air)

fc_pe = fc_cutoff_hz(a_pe, b_pe, er_pe)

print(f"fc (air): {fc_air/1e6:.2f} MHz")

print(f"fc (PE ): {fc_pe/1e6:.2f} MHz")

print()

# Power vs frequency (use 100 MHz)

f_test = 100e6

p_air = power_vs_frequency(ED_AIR, f_test)

print(f"P ~ K*(Ed^2)/f at 100 MHz: {p_air:.3e} (scaled units)")

print()

# Attenuation – conductor trend

f_loss = 200e6

alpha_air = attenuation_conductor_nepers_per_m(f_loss, coax_air)

alpha_pe = attenuation_conductor_nepers_per_m(f_loss, coax_pe)

print(f"Conductor attenuation at 200 MHz (trend):")

print(f" α_air ≈ {alpha_air:.6f} nepers/m")

print(f" α_pe ≈ {alpha_pe:.6f} nepers/m")

print()

# Thermal conduction

To = 25.0 + 273.15 # K

Ti = 120.0 + 273.15 # K

L = 1.0 # m

Q_air = heat_transfer_rate_Q(a_air, b_air, coax_air.k_thermal, L, To, Ti)

Q_pe = heat_transfer_rate_Q(a_pe, b_pe, coax_pe.k_thermal, L, To, Ti)

print(f"Heat transfer rate Q (air): {Q_air:.2f} W")

print(f"Heat transfer rate Q (PE ): {Q_pe:.2f} W")

print()

# Max E-field at inner surface for a given voltage (e.g., 1 kV)

V_test = 1000.0

Emax_air = max_surface_e_field(V_test, a_air, b_air)

Emax_pe = max_surface_e_field(V_test, a_pe, b_pe)

print(f"Emax at inner surface (air, 1kV): {Emax_air:.2e} V/m")

print(f"Emax at inner surface (PE , 1kV): {Emax_pe:.2e} V/m")

if __name__ == "__main__":

demo()

Coaxial cable, power, transmission line

Coaxial cable, power, transmission line

0 comment

0 comment

29 Nov, 2025

29 Nov, 2025

Engineer Duru

0 comment